The epidermis is the outermost skin layer that protects the body against environmental damage. It plays a crucial role in barrier function, hydration regulation, and immune defense against pathogens.

Layers of the epidermis include stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, and stratum corneum. Each layer contributes to cell regeneration, keratinization, and barrier strength.

Stratum basale is responsible for new skin cell formation, while stratum corneum provides a protective shield against external stressors. These processes maintain healthy and resilient skin over time.

Epidermal health depends on hydration, nutrition, and skincare. Proper cleansing, sun protection, and moisturization support natural regeneration and minimize premature aging or dermatological conditions.

| Definition | The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin and acts as a barrier protecting the body from external factors. |

| Structure | Primarily composed of keratinocytes, but also includes melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells. |

| Layers | 1. Stratum Corneum (horny layer)

2. Stratum Lucidum (only on palms and soles) 3. Stratum Granulosum (granular layer) 4. Stratum Spinosum (spiny layer) 5. Stratum Basale (basal layer) |

| Functions | – Provides physical protection – Prevents water loss – Produces melanin against UV radiation – Forms a barrier against microorganisms |

| Renewal Period | The epidermis renews itself on average every 28 days. |

| Blood Circulation | The epidermis contains no blood vessels; nutrients and oxygen diffuse from the dermis. |

| Associated Diseases | Psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, melasma, skin cancers (e.g., basal cell carcinoma, melanoma). |

What is the Epidermis?

Some people might think the epidermis is just “unnecessary tissue made up of dead cells.” This is a complete misconception. Yes, the uppermost layer (the stratum corneum) is largely composed of dead cells, but even these “dead” cells fulfill very important roles. Without them, our skin would quickly dry out, crack, and open the door to infections. So rather than seeing the epidermis as a mere “layer,” we should regard it as a “life-sustaining armor.”

This structure we call the epidermis varies in thickness from about 0.05 mm (in thin areas like the eyelids) to 1.5 mm (in thick areas like the palms and soles). The thickness differs by region because various parts of the body are exposed to different levels of friction, pressure, or sunlight. If the epidermis on our soles were as thin as on our eyelids, everyday life would be far more uncomfortable. So the epidermis is specialized to suit the needs of each part of the body.

How Many Layers Does the Epidermis Have?

The epidermis is made up of five main layers, moving from the outside in:

- Stratum Corneum (Horny Layer)

- Stratum Lucidum (Clear Layer)

- Stratum Granulosum (Granular Layer)

- Stratum Spinosum (Spiny Layer)

- Stratum Basale (Basal Layer)

However, these layers are not always visually distinct. For instance, the Stratum Lucidum is only present in “thick skin” areas such as the palms and soles; in other regions, it is often too thin to be noticeable or may be absent. This ensures an extra protective layer in specialized areas where needed.

What is the Stratum Corneum (Horny Layer) and Why Is It Important?

The Stratum Corneum is the outermost layer in direct contact with the external environment. It contains keratinized (keratin-filled) cells, often referred to as “dead” but in fact very valuable. These cells, known as corneocytes, stack like bricks in a castle wall to form a solid barrier. This layer has two main features:

Strong Protective Barrier: Much of the firmness and solidity you feel when touching the skin comes from this layer. It is waterproof; in other words, you don’t swell up like a water-filled sponge when you take a shower. Similarly, it restricts water and microorganisms from passing inwards.

Continuous Renewal and Shedding: Corneocytes in the Stratum Corneum eventually detach from the surface and are shed. This process is called “desquamation.” The dust we see around us often largely consists of these dead skin cells. Our skin continuously replaces them with fresh, new cells.

When you frequently wash your hands or use too much soap, you notice your skin drying out. That’s because the lipid (fat) layer and moisturizing factors in the Stratum Corneum are washed away, weakening the natural moisture barrier. You might see cracks or flaking as a result. This is why we use moisturizers—to help restore lost hydration in this layer.

Sometimes, this layer can thicken excessively (e.g., on the heels). This can lead to cracks or calluses on the soles of the feet. We often use a pumice stone to thin this layer out. If not properly cared for, dryness persists, and cracks can deepen, causing pain and even increased infection risk.

Is the Stratum Lucidum (Clear Layer) Everywhere?

The Stratum Lucidum is an extremely thin, translucent layer generally found in areas of thick skin such as the palms and soles. Think of it as an extra pane of glass on a window, providing a bit more protection and adding thickness to the skin. While it’s not very noticeable on other parts of the body, it helps make our palms and soles more resistant to friction or pressure.

You can feel the difference between the back of your hand and your palm. The palm’s skin is thicker, tougher, and generally less sensitive. Because our palms constantly undergo friction and mechanical pressure (like carrying heavy bags, using tools), they need an extra layer. If your palm skin were as thin as the back of your hand, you’d feel pain and irritation much more easily during everyday activities.

How Does the Stratum Granulosum (Granular Layer) Function?

The Stratum Granulosum can be seen as the “workshop” of the epidermis. Cells here increase keratin production and secrete lipid-filled granules (lamellar bodies), strengthening the waterproof barrier that prevents water loss in the upper layers. These cells start reorganizing their internal structures to transition into corneocytes.

In the Granular Layer, cells produce “waterproof cement” that holds corneocytes together in the upper layers. This “cement” gives the corneocytes a more robust defense against the outside world. In conditions of increased skin dryness or flare-ups of eczema, this layer’s lipid production and cellular organization may be compromised, weakening the skin’s protective function and often resulting in cracking, irritation, or allergic reactions.

Why Is It Called the Stratum Spinosum (Spiny Layer)?

The Stratum Spinosum, or spiny layer, is named for the spiny or prickly appearance of the cells when viewed under a microscope. This spiny look is the result of “desmosomes,” which are junctions that tightly bind the cells to each other. Like water droplets held together by surface tension, these cells hold fast to each other to keep the epidermis intact and sturdy.

Also found in the Stratum Spinosum are Langerhans cells, important for the skin’s immune defense. When they encounter harmful microorganisms or foreign substances, they act as “guards,” alerting the immune system. This enables the skin to respond quickly whenever it’s cut or irritated; without these cells, even a minor cut could lead to serious infections. The cell connections and Langerhans cells in this layer help contain damage before it compromises the entire skin barrier.

How Does the Stratum Basale (Basal Layer) Provide Renewal?

Now we arrive at the “birthplace” of the epidermis: the Stratum Basale. This layer is like a “seedbed” for new cells. Keratinocytes here divide and migrate toward the surface layers. As they travel, they differentiate into corneocytes, ultimately taking their place in the Stratum Corneum.

However, the Stratum Basale is not just keratinocytes; it also houses melanocytes, cells that produce the pigment melanin. As melanin production increases, your skin darkens and is better protected from sunlight (especially UV rays). Tanning is essentially increased melanin production by melanocytes. But prolonged and unprotected sun exposure can push melanocytes into overdrive, leading to uneven pigmentation or a higher risk of skin cancer. Hence the advice to use sunscreen regularly and avoid prolonged exposure to intense midday sun.

The Stratum Basale also contains Merkel cells, which contribute to touch sensation. These cells use receptors that detect pressure and vibration to send signals to the brain, enhancing our ability to perceive touch. For example, when you lightly press a needle tip onto your finger, Merkel cells are among the first to perceive that sensation.

What Is the Significance of the Epidermis in Skin Health?

Although it’s the most superficial layer of the skin, the epidermis is critical for many functions. For those who ask, “Why is this so important?”, here are a few reasons:

- Barrier Function: Polluted air, germs, chemicals, dust—all these harmful elements are thwarted by the epidermis’s barrier from easily infiltrating your skin and internal organs.

- Moisture Retention: Especially in the Stratum Corneum, the epidermis acts like a lock preventing the evaporation of water from our bodies. Once that lock is damaged, our skin becomes dry, cracked, and more prone to conditions like eczema.

- UV Protection: Thanks to melanocytes, the epidermis can absorb or reflect harmful UV rays, protecting underlying cells. Excessive UV exposure can lead to premature aging and skin cancer.

- Immune Defense: Langerhans cells are the first line of defense against microorganisms trying to invade. At any sign of danger, they activate the immune alarm system.

- Sensory Functions: Receptors like Merkel cells help us sense touch and pressure.

If your skin has issues, it’s not just an aesthetic problem; damage to the epidermis also weakens your immune defenses. That’s why skin health is closely tied to overall health.

What Cell Types Are Found in the Epidermis?

The epidermis can be described as a “miniature ecosystem.” Different types of cells work together here:

- Keratinocytes: The majority of epidermal cells, producing keratin, which plays a key role in the skin’s mechanical strength.

- Melanocytes: Cells that produce pigment, determining skin tone and providing protection against UV rays.

- Langerhans Cells: The “patrolling guards” of the immune system. They recognize antigens, capture them, and carry them to lymph nodes to initiate an immune response.

- Merkel Cells: Involved in the sense of touch, helping detect subtle pressure and gentle contact.

- Basal Cells (Stem Cells): Located in the Stratum Basale, constantly dividing to produce new keratinocytes and renew the epidermis.

All these cells function together like instruments in an orchestra. If one instrument is out of tune, the overall “music” of the skin can become disrupted.

How Does the Epidermis Prevent Water Loss?

Preventing skin dryness and unwanted water exchange with the environment is one of the epidermis’s most crucial tasks. It employs several “safeguards” to achieve this:

Lipid Barrier: The cells in the Stratum Corneum are surrounded by a “cement” made of ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids. This “cement” is water-repellent, much like grout in a wall.

Natural Moisturizing Factors (NMF): Substances like amino acids, urea, and lactic acid attract water and help retain it in the skin, preserving its suppleness.

Continuous Cell Renewal: As the skin renews, damaged or aged cells are replaced by new ones, maintaining an intact barrier.

Water-Holding Capacity: Through unique proteins and ionic balances, the skin can trap water, keeping it firm and vibrant.

Especially in cold or very dry climates, our skin dries out faster due to low humidity. If the skin barrier is weak, moisture loss increases, resulting in flaking, cracking, or itching. Hence the recommendation to use moisturizers more regularly in winter, to take warm (not hot) short showers, and even to use a humidifier in dry indoor environments.

How Can We Support the Epidermis in Skincare?

By caring for our skin daily, we help the epidermis perform its functions better. Think of this as a “skin health guide”:

Regular Cleansing:

- Overly hot and long showers can disrupt the skin’s lipid barrier. Shorter showers with lukewarm water are preferable.

- Use mild cleansers that maintain skin’s pH balance rather than harsh soaps.

Moisturizing:

- After washing, bathing, or handwashing, it’s important to apply moisturizer.

- Body lotions, creams, or ointments enriched with barrier-supporting ingredients (e.g., ceramides, hyaluronic acid) are beneficial.

Sun Protection:

- Sunscreen (SPF 30 or higher) is recommended not just in summer but whenever you are exposed to the sun.

- Limiting time in direct sunlight, especially between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., is another protective measure.

Healthy Diet:

- A diet rich in antioxidants (fruits, vegetables, healthy fats) protects skin cells from oxidative stress.

- Adequate protein intake provides amino acids necessary for keratin production.

Hydration:

- Drinking enough water is essential for efficient cell function and overall body processes.

- Moderation with diuretic beverages like caffeine or alcohol is advisable, as they can increase water loss.

Lifestyle Habits:

- Smoking impairs blood flow and oxygenation of the skin, leading to premature aging.

- Adequate sleep is crucial for cell renewal. Sleep deprivation can make your skin appear dull and lifeless.

Following these suggestions helps protect and strengthen the epidermis while supporting overall skin health. Of course, if you have persistent or severe skin issues (e.g., eczema, psoriasis, allergic dermatitis), it’s best to see a dermatologist. Sometimes home remedies aren’t enough, and professional assistance is required.

How Does the Epidermis Change With Age?

As with the rest of our body, the skin undergoes changes over time. The epidermis can thin out, and its renewal pace can slow. In childhood and adolescence, cell turnover is rapid, but in older age, this cycle slows. Some research suggests that as we age, the turnover cycle can extend to as long as 60 days.

The number and function of melanocytes also change, leading to the appearance of pigmentation spots, often referred to as “age spots” or “sun spots,” commonly found on the hands and face. In some areas, pigment loss occurs, creating white or very light patches.

Additionally, the skin’s immune capacity can decrease, meaning the number and activity of Langerhans cells are reduced, leaving the skin more susceptible to infections. Tailoring your skincare routine to this aging process—using products that protect the skin barrier and seeking professional advice when needed—becomes increasingly vital.

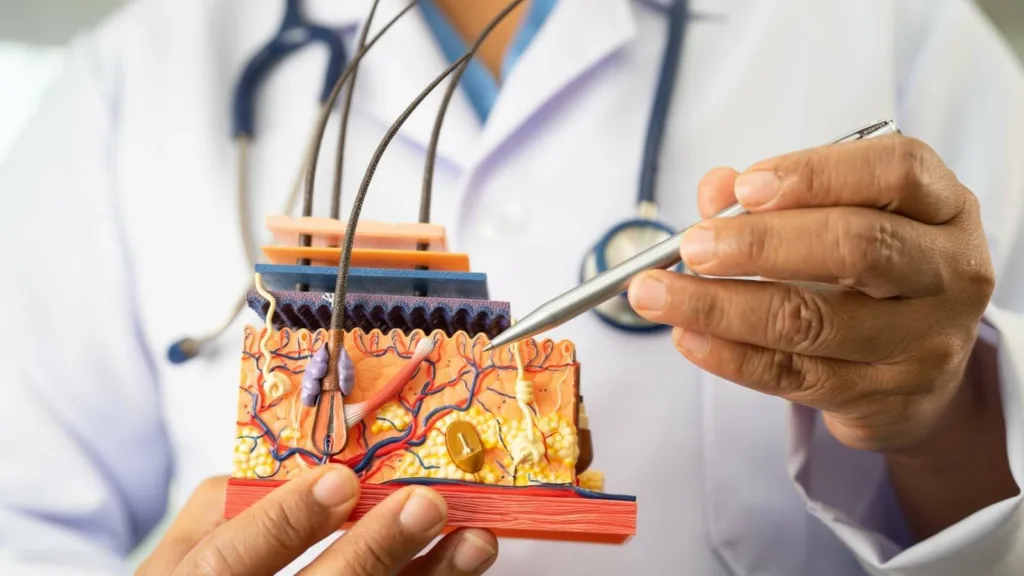

How Does the Epidermis Interact With the Other Layers (Dermis and Hypodermis)?

Our skin is not just the epidermis; it also includes the dermis and the hypodermis (subcutaneous tissue). They operate in constant interplay, like a well-functioning “team”:

Dermis: Contains connective tissue, blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, and sweat glands. It provides nourishment, hydration, and waste removal for the epidermis. Rich in collagen and elastin, it gives the skin elasticity and firmness.

Hypodermis: Composed of adipose (fat) tissue. It helps with insulation and acts as a “shock absorber” for internal organs. It also serves as an energy reserve.

If the epidermis barrier weakens, the dermis and hypodermis become more prone to infection and damage. For example, in serious burns or injuries, damage to the upper layers of the skin can more easily compromise the tissues below. Conversely, if blood circulation in the dermis is impaired, the epidermis may not get adequate nutrients, leading to dryness, flaking, and delayed healing. Thus, these three layers essentially form an interconnected ecosystem.

Diversity of the Epidermis in Different Body Areas

The thickness and cell structure of the epidermis vary by location:

- Eyelids: Extremely thin epidermis. The skin around the eyes is among the most delicate areas and needs special care.

- Soles of the Feet: Very thick epidermis. The feet carry our body weight all day, requiring extra protective thickness. The presence of a prominent Stratum Lucidum here is no coincidence.

- Palms: Resistant to friction; has a different distribution of oil and sweat glands.

This variation stems from each region’s need to adapt to mechanical and chemical factors. Essentially, our body “customizes” epidermal features to suit each area’s functional requirements.

Which Skin Problems Directly Affect the Epidermis?

Many skin issues directly involve or first manifest in the epidermis:

- Eczema (Dermatitis): This condition with redness, itchiness, and dryness can occur when the epidermis’ barrier function is disrupted.

- Psoriasis: Characterized by an abnormally high cell turnover rate, leading to thick, scaly plaques.

- Acne: Although largely involving hair follicles and sebaceous glands, the epidermis also plays a role; excessive keratin production can clog follicles.

- Melasma, Lentigo (Pigmentation Spots): Result from irregular pigment production by melanocytes.

- Skin Cancers (Basal Cell Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Melanoma): These arise from cells in the epidermis. Excessive sun exposure and genetic factors can contribute to their development.

Some of these issues may appear purely cosmetic, but in conditions like eczema or psoriasis, a compromised barrier can lower the skin’s defenses and increase infection risk. Acne can also introduce infection risks. Skin cancers, if not detected early, can become life-threatening. Hence it’s crucial to monitor any unusual changes in the epidermis and consult a dermatologist if needed.

How Does the Epidermis Heal?

When you get a cut, scrape, or minor burn, the epidermis goes into alert mode, communicating with the dermis and blood vessels to start the healing process. The process occurs in several stages:

- Clotting (Hemostasis): Immediately after injury, blood vessels constrict, and platelets gather at the wound to form a clot.

- Inflammation: White blood cells (leukocytes) and later macrophages gather around the wound to clear out bacteria or foreign material.

- Proliferation (New Tissue Formation): New blood vessels (angiogenesis) supply more oxygen and nutrients. Keratinocytes from the Stratum Basale migrate to the wound site to help close the wound.

- Maturation (Remodeling): Newly formed tissue becomes stronger, and the epidermis thickens. Collagen fibers reorganize for greater resilience.

If the wound is only in the epidermis, it usually heals without scarring. Deeper wounds that extend into the dermis can lead to scar formation because connective tissue is damaged, and the healing process takes a different course. The epidermis has a strong renewal capacity, but the healing outcome depends on how deep and wide the wound is.

Why Is Some Skin More Sensitive or More Resilient?

The epidermis is shaped by genetics, environmental factors, and lifestyle. Some people’s skin is thicker and oilier, while others have drier, more sensitive skin. Contributing factors include:

- Genetics: Our genes, inherited from our parents, largely determine skin structure and pigmentation levels. Some individuals naturally have darker skin, offering more UV protection, while others are prone to allergies or sensitivities.

- Hormonal Changes: Conditions such as puberty, pregnancy, or menopause affect oil production, moisture balance, and pigmentation.

- Climate and Geography: Humidity, temperature, and sun intensity influence the skin. In humid environments, skin doesn’t dry out as easily, but in very hot regions, sweating and mineral loss can become issues.

- Diet: A diet rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants supports the epidermis’ renewal capacity. Poor nutrition can lead to a dull, thin, and irritation-prone complexion.

- Skincare Habits: Using harsh cosmetics or neglecting cleaning and moisturizing routines can weaken the barrier. Over-exfoliating or using products with strong chemicals can also heighten sensitivity.

Instead of asking “Why is my skin like this?” it’s more helpful to ask how to care for it better. We can’t change our genetic inheritance, but we can control many environmental factors like lifestyle and skincare routines.

How Do the Sun and Other External Factors Harm the Epidermis?

Sunlight (especially UVA and UVB) is one of the most damaging external factors for the epidermis. UV rays can directly affect the DNA of keratinocytes and melanocytes, increasing the long-term risk of skin cancer. Premature aging (wrinkles, spots) is also strongly linked to sun damage.

Other factors include:

Pollution: Free radicals in polluted air cause oxidative stress to skin cells, weakening the epidermis’s regenerative capacity.

Chemical Irritants: Found in cleaning products, cosmetics, or industrial environments, these can wear down the epidermal barrier.

Extreme Cold or Heat: Both extremes can increase skin’s moisture loss. Heat leads to sweating and loss of salts and minerals; cold can cause cracking and dryness.

While the epidermis activates its defenses, prolonged or intense exposure may overwhelm these defenses. Therefore, using sunscreen, paying extra attention to skincare in highly polluted areas, and wearing protective gloves/clothing when handling chemicals all help mitigate this damage.

Does the Epidermis Have a Biological Rhythm?

Like nearly all organs in our body, the epidermis has a “circadian rhythm.” Research shows that cell division and renewal are more active in the epidermis at night. During the day, the skin endures stress from UV rays and pollution, while nighttime is prime time for damage repair.

This is why many night creams or restorative serums are designed to work while you sleep, a period when the skin is in repair mode. Getting sufficient sleep (7-8 hours a night) is essential not just for overall health but also for healthy skin. Chronic lack of sleep can cause dark under-eye circles, a dull complexion, and more prominent wrinkles.

What Natural and Medical Methods Strengthen the Epidermis?

Natural Methods:

- Aloe Vera, Chamomile, Green Tea Extracts: Have anti-inflammatory properties that can soothe mild irritations.

- Honey Masks: Honey is a natural humectant. Used as a face mask, it can strengthen the skin’s moisture barrier.

- Coconut Oil, Olive Oil: High in fatty acids that can moisturize dry areas. Use caution if your skin is prone to acne.

Medical/Professional Methods:

- Chemical Peels: AHA (alpha hydroxy acids) or BHA (beta hydroxy acids) peels remove the top layer, encouraging fresh cells to surface.

- Laser Treatments: Laser sessions can speed up epidermal renewal and stimulate collagen production.

- Medical Creams: Retinoid-based creams regulate keratinization and help with acne, pigmentation, and fine lines.

Each method’s effectiveness varies depending on your skin type, age, and specific concerns. Medical techniques should be supervised by a professional, as inappropriate use can damage the skin barrier.

Common Misconceptions About the Epidermis

“The epidermis is completely dead, so there’s no need for care.”

Wrong: While the Stratum Corneum includes dead cells, the deeper layers, especially the Stratum Basale, actively proliferate and renew themselves. Skincare maintains the health of all these layers.

“Sunscreen is only necessary in summer.”

Wrong: UV rays can harm the skin even on cloudy days. Applying sunscreen to exposed areas is recommended virtually any time you go outside.

“Frequent exfoliation makes the skin smoother.”

Wrong: Excessive exfoliation can damage the Stratum Corneum and even deeper layers, leading to increased sensitivity, redness, and irritation.

“Everyone should have the same skincare routine.”

Wrong: Skin needs vary from person to person. Some have oily skin, some have dry skin, some are prone to pigmentation, others to breakouts. Products and methods must be tailored individually.

The Epidermis: Your First Line of Defense

As the most superficial layer constantly exposed to external factors, the epidermis is like an “invisible hero” that continuously renews itself while protecting you. These five layers (Stratum Basale, Spinosum, Granulosum, Lucidum, and Corneum) work in remarkable harmony. Each layer performs a specific task: some produce cells, others reinforce immune defense, others thicken the skin to withstand friction.

When you practice skincare, you’re effectively supporting all these layers. Protecting yourself from damaging factors (UV rays, pollution, chemicals), maintaining hydration, eating a balanced diet, and living a healthy lifestyle help the epidermis perform its functions.

If your epidermis is happy, you’re likely to have brighter, healthier-looking skin. Remember that skin health isn’t just about appearance; it also impacts overall health. Many conditions begin when the skin’s protective function weakens. Preserving the integrity of the epidermis is a vital key to feeling good and aging well.

Op. Dr. Erman Ak is an internationally experienced specialist known for facial, breast, and body contouring surgeries in the field of aesthetic surgery. With his natural result–oriented surgical philosophy, modern techniques, and artistic vision, he is among the leading names in aesthetic surgery in Türkiye. A graduate of Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Dr. Ak completed his residency at the Istanbul University Çapa Faculty of Medicine, Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery.

During his training, he received advanced microsurgery education from Prof. Dr. Fu Chan Wei at the Taiwan Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and was awarded the European Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Qualification by the European Board of Plastic Surgery (EBOPRAS). He also conducted advanced studies on facial and breast aesthetics as an ISAPS fellow at the Villa Bella Clinic (Italy) with Prof. Dr. Giovanni and Chiara Botti.

Op. Dr. Erman Ak approaches aesthetic surgery as a personalized art, tailoring each patient’s treatment according to facial proportions, skin structure, and natural aesthetic harmony. His expertise includes deep-plane face and neck lift, lip lift, buccal fat removal (bichectomy), breast augmentation and lifting, abdominoplasty, liposuction, BBL, and mommy makeover. He currently provides safe, natural, and holistic aesthetic treatments using modern techniques in his private clinic in Istanbul.