Postoperative constipation occurs as a result of slowed bowel movements caused by a combination of factors such as anesthetic medications used, drugs given for pain control, immobility during the recovery period, and the body’s natural stress response to surgery. Frequently seen after aesthetic surgery, this condition is more than just a comfort issue; by creating the need to strain, it can become a significant factor that risks the integrity of the carefully achieved surgical result. The management and prevention of this problem are possible through conscious steps taken during the recovery process, modern pain control approaches, and proper nutrition and fluid intake that begin in the preoperative period.

What Causes Postoperative Constipation?

It is not possible to attribute postoperative constipation to a single culprit. This condition is often like a “perfect storm” created by multiple factors coming together. During the surgical process, your body is exposed to many internal and external influences, and your digestive system is not spared from these effects. To better understand this complex situation, let’s examine the four main factors that set the stage for constipation: anesthesia, painkillers, immobility, and the body’s natural stress response to surgery.

The first of these factors, general anesthesia, is the first domino that initiates the constipation process. The medications given to put you to sleep during surgery and prevent you from feeling pain not only affect your brain functions but also temporarily put the smooth muscles in your digestive system into “sleep mode.” The rhythmic contractions that move food forward in the intestines, known as peristalsis, slow down or completely stop for a while. This temporary intestinal sluggishness sets the first step toward constipation. Even when the effects of anesthesia begin to wear off, it takes time for the intestines to return to their normal rhythm. While the small intestines recover within a few hours, it may take a day or two for the stomach and especially the large intestine to start functioning at full capacity.

The factor that continues the process and often worsens the condition the most is the use of strong painkillers to control postoperative pain. These medications, especially those known as opioids, are very effective at relieving pain but have significant slowing effects on the digestive system. By binding not only to pain centers in the brain but also to specific receptors densely located in the intestinal wall, they trigger a series of adverse effects:

- Strong painkillers affect the intestines in several different ways.

- They slow the intestines’ natural propulsive movements.

- They cause more water than normal to be absorbed from the stool.

- They reduce gastric and intestinal secretions that aid digestion.

- They increase the tension of the muscles in the anal region, making defecation difficult.

The most critical point regarding these drugs is that, although the body may adapt over time to other side effects (such as drowsiness), it does not develop tolerance to their constipating effect. In other words, the risk of constipation persists as long as you use the medication.

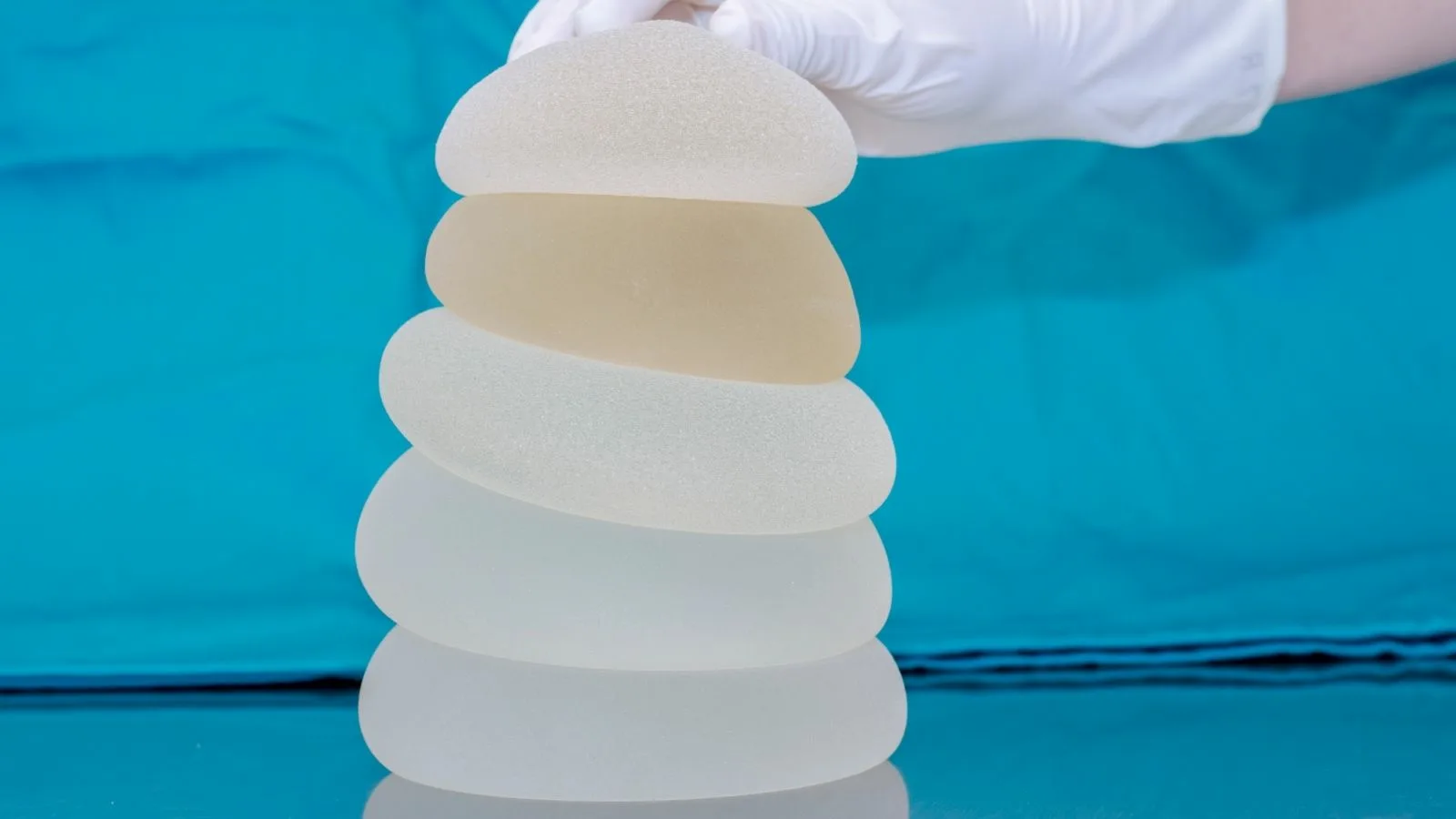

The third part of the equation is immobility. Physical activity is the intestines’ best friend. Especially after procedures like abdominoplasty, breast aesthetics, or comprehensive body contouring, you need to rest for a certain period and avoid strenuous activities to protect the sutures and ensure proper healing. However, this mandatory rest eliminates the natural stimulating effect of gravity and movement on the intestines. Slowed blood circulation and reduced physical activity also cause the digestive system to slow down.

What Can Be Done Preoperatively to Reduce the Risk of Constipation?

The most effective weapon in combating postoperative constipation is a proactive approach. Instead of trying to solve the problem after it appears, you can significantly reduce this risk with simple yet effective measures taken even before you lie down on the operating table. This means taking control of your recovery process from the very beginning.

The first step in this process is the consultation you will have with your doctor before surgery. In this discussion, topics such as your normal bowel habits and any history of chronic constipation are reviewed in detail. If you are already prone to constipation, you will be informed that this condition may be more pronounced after surgery, and a personalized prevention plan will be created for you. The purpose of this conversation is not to worry you, but rather to make you aware and an active participant in your recovery process.

The most important part of this preparation phase is optimizing your diet and fluid intake. Small dietary changes you make during the week before surgery can make a big difference by increasing your body’s resilience.

Some fiber-rich foods recommended to add to your diet in the week before surgery are:

- Oatmeal

- Rye bread

- Whole wheat bread

- Lentils

- Chickpeas

- Kidney beans

- Apple

- Pear

- Prunes

- Broccoli

- Carrot

- Spinach

Similarly, there are some foods you should reduce in this period:

- Ultra-processed packaged products

- White bread

- White rice

- White pasta

- Heavy cheese and dairy products

- Red meat

Another topic as important as nutrition is adequate fluid intake. When the body is dehydrated, it draws more water from the stool in the intestines, causing the stool to harden and making its passage more difficult. In the days before surgery, you should aim to drink at least 2–2.5 liters of water per day. If you have difficulty drinking water, herbal teas or freshly squeezed unsweetened fruit juices can be good alternatives. However, caffeinated beverages such as coffee, black tea, and cola have a diuretic effect and can increase water loss from the body, so it is advisable to limit their consumption during this period:

In some cases, especially in patients with a history of chronic constipation, starting an over-the-counter stool softener one or two days before surgery may be recommended. The idea here is to soften the intestinal contents before the effects of anesthesia and painkillers begin, making things easier. However, it should be known that this practice is not necessary for everyone and that its effectiveness is not as strong as the most basic strategies—proper nutrition and adequate fluid intake. The most accurate decision on this matter will be made by your doctor after evaluating your risk factors. Priority should always be given to natural methods before medications.

How Does Postoperative Constipation Resolve?

When you encounter constipation during the recovery period, there are many effective and safe methods you can apply without panicking. Treatment should be approached with a multifaceted strategy consisting of non-drug natural methods and modern pain control strategies. The goal is not only to eliminate the symptom but also to address the root causes of the problem.

Is It Possible to Manage Constipation Without Medication?

Yes, it is absolutely possible, and these should be the first methods to try. Non-drug solutions help the body regain its natural rhythm and carry no risk of side effects.

First and foremost is early mobilization. Although resting is important in the postoperative period, this should not mean lying down constantly. As soon as your doctor permits—usually on the first day after surgery—getting up and taking short, frequent walks in the room or corridor is one of the strongest stimuli that promote intestinal motility (peristalsis). Walking not only gets the intestines working but also speeds up blood circulation, reducing the risk of more serious complications such as blood clots (deep vein thrombosis) in the legs.

Maintaining adequate fluid intake is also of critical importance. After surgery, the body needs water to repair itself. Drinking plenty of water keeps the stool soft, making its passage easier. In addition to water, prune juice, which contains sorbitol—a natural laxative—can be quite beneficial during this period. A glass of warm prune juice on an empty stomach in the morning can gently stimulate your bowels.

Your diet also affects your recovery speed. Once your doctor allows oral feeding, you should gradually reintroduce fibrous foods into your diet. Instead of large and heavy meals, eating small and frequent meals keeps the digestive system working continuously without straining it. Boiled vegetables, soups, compotes, and fresh fruits can be good starting options.

Why Is Modern Pain Control So Important in Preventing Constipation?

The most revolutionary and effective strategy in preventing postoperative constipation is minimizing the need for strong (opioid) painkillers. Modern anesthesia and surgical approaches aim to control pain by using multiple methods that act through different mechanisms, rather than suppressing it with a single drug. This “multimodal pain management” approach dramatically reduces the use of opioids, the most stubborn cause of constipation.

This modern approach consists of a combination of several different methods.

- Preemptive analgesia before surgery

- Regional nerve blocks (such as TAP, PECS blocks)

- Long-acting local anesthetics

- Regular, non-opioid medications after surgery

One of the cornerstones of this approach is the regional nerve blocks administered during surgery. For example, in an abdominoplasty, a technique called the “TAP block,” which targets the nerves in the abdominal wall, can numb only the surgical area for hours. Similarly, with the “PECS block” used in breast surgeries, pain signals in the chest area are blocked. Another effective method is the injection of long-acting local anesthetics into the surgical field. These special medications can maintain their effects for up to 72 hours, allowing you to pass the first three days—which are the most painful—almost pain-free.

Thanks to these advanced techniques, what you will usually need in the postoperative period is simply basic, non-opioid pain relievers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Strong opioids are reserved only as “rescue medicine” for sudden and severe pain attacks when these basic drugs are insufficient. This strategy not only reduces the risk of constipation but also eliminates other side effects caused by opioids, such as nausea, excessive drowsiness, and dizziness, offering a much more comfortable and faster recovery process. Although the cost of these advanced techniques may seem higher than standard methods, when you consider the time, effort, and additional costs required to manage constipation and other complications, they are, in fact, an invaluable investment that protects your surgical outcome and comfort.

What Options Are Available When Medication Is Needed for Constipation?

If constipation develops despite all preventive measures and natural methods, medical assistance may be necessary. In this case, a step-by-step pharmacological treatment approach is usually adopted, progressing from the simplest to the more potent options. The aim is to start with the gentlest option with the least side-effect potential and only move on to more potent treatments when necessary. It is important to consult your doctor or pharmacist before using these medications.

Stool Softeners

These medications are used more to prevent constipation or manage very mild symptoms than to treat it.

- Mechanism of Action: They reduce the surface tension of the stool, allowing water to penetrate and soften it.

- Examples: Capsules or syrups containing docusate sodium.

- Intended Use: Keeping the stool soft, especially in cases where straining is absolutely undesirable (such as after abdominoplasty).

- Important Note: They do not directly stimulate the intestines, so they are often insufficient to resolve established constipation.

Osmotic Laxatives

This group is often the first-line pharmacological option in cases of established constipation.

- Mechanism of Action: They remain within the intestine and draw water into the intestinal lumen from surrounding tissues. The increased water softens the stool and increases its volume, which stimulates the intestines’ natural contractions.

- Examples: Polyethylene glycol (often in powder form mixed with water) or lactulose and magnesium hydroxide (in syrup form).

- Intended Use: To resolve mild to moderate constipation safely and effectively.

- Onset of Action: They usually act slowly and gently within 1 to 3 days.

Stimulant Laxatives

These medications are a stronger option used when other methods fail.

- Mechanism of Action: They directly stimulate the nerves in the intestinal wall, triggering strong, propulsive contractions (peristalsis).

- Examples: Tablets or drops containing senna or bisacodyl.

- Intended Use: Stubborn constipation that does not respond to other treatments.

- Important Note: They are more likely to cause abdominal cramps and are strictly suitable for short-term use. Long-term use can lead to intestinal sluggishness.

Rectal Treatments (Suppositories or Enemas)

These methods are reserved for situations where stool is impacted in the rectum and urgent relief is needed.

- Mechanism of Action: Suppositories provide local lubrication and stimulation, while enemas introduce fluid into the rectum to soften impacted stool and trigger a strong evacuation reflex.

- Examples: Suppositories containing glycerin or bisacodyl, ready-to-use enema kits.

- Intended Use: Severe fecal impaction or urgent situations where no response is obtained with oral laxatives.

- Onset of Action: They usually act very quickly, within 15 to 60 minutes.

Especially in the postoperative period, it is generally safer to avoid bulk-forming laxatives (such as psyllium). For these laxatives to be effective, they must be taken with plenty of water. In a postoperative patient who may not be able to consume enough fluids, these agents can absorb water and form a hard mass within the intestine, potentially worsening constipation and leading to a dangerous intestinal obstruction.

Which Symptoms Indicate a Problem Beyond Constipation?

When managing postoperative constipation, it is vital to know which symptoms are normal and manageable and which are “red flags” requiring urgent medical attention. Being able to make this distinction allows you to detect potential serious complications early and take precautions.

Normal postoperative constipation symptoms are usually uncomfortable but not dangerous. These include decreased frequency of bowel movements, bloating, gas, and mild abdominal discomfort. However, some symptoms may indicate a condition more serious than simple constipation, such as an intestinal obstruction or severe intestinal sluggishness (ileus).

If you experience any of the following “red flag” symptoms, it is critical not to consider the situation as simple constipation and to seek medical help immediately:

- Severe and progressively worsening abdominal pain

- Visible, firm abdominal distension

- Inability to pass gas

- Persistent nausea and vomiting (especially bilious or foul-smelling)

- No bowel movement at all for more than 4–5 days despite applied treatments

- Fever or chills

- Blood in the stool or rectal bleeding

These symptoms may herald a mechanical obstruction or circulatory disorder in the intestines and should be evaluated in an emergency department without delay.

Additionally, although not directly related to aesthetic surgery, it is useful to know the symptoms of Cauda Equina Syndrome, an extremely rare but urgent neurological condition that can present with bowel dysfunction. This condition arises from compression of the bundle of nerves at the lower end of the spinal cord and requires immediate intervention to prevent permanent damage.

The alarming symptoms of Cauda Equina Syndrome are as follows:

- Severe low back pain

- Pain, numbness, or weakness radiating down both legs

- Loss of sensation or numbness in the “saddle area,” including the genitals, anus, and inner thighs

- New-onset urinary incontinence or inability to urinate (loss of bladder control)

- New-onset fecal incontinence (loss of bowel control).

Op. Dr. Erman Ak is an internationally experienced specialist known for facial, breast, and body contouring surgeries in the field of aesthetic surgery. With his natural result–oriented surgical philosophy, modern techniques, and artistic vision, he is among the leading names in aesthetic surgery in Türkiye. A graduate of Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Dr. Ak completed his residency at the Istanbul University Çapa Faculty of Medicine, Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery.

During his training, he received advanced microsurgery education from Prof. Dr. Fu Chan Wei at the Taiwan Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and was awarded the European Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Qualification by the European Board of Plastic Surgery (EBOPRAS). He also conducted advanced studies on facial and breast aesthetics as an ISAPS fellow at the Villa Bella Clinic (Italy) with Prof. Dr. Giovanni and Chiara Botti.

Op. Dr. Erman Ak approaches aesthetic surgery as a personalized art, tailoring each patient’s treatment according to facial proportions, skin structure, and natural aesthetic harmony. His expertise includes deep-plane face and neck lift, lip lift, buccal fat removal (bichectomy), breast augmentation and lifting, abdominoplasty, liposuction, BBL, and mommy makeover. He currently provides safe, natural, and holistic aesthetic treatments using modern techniques in his private clinic in Istanbul.