Why does the digastric muscle shape the neck?

To understand your profile, you have to visualize what lies beneath the skin. The digastric muscle is a unique structure that essentially acts as a sling or hammock under your jaw. It has two distinct sections, or “bellies,” but for the purpose of neck aesthetics, we are primarily concerned with the anterior belly. These muscles run from the tip of your chin back toward the hyoid bone in the neck.

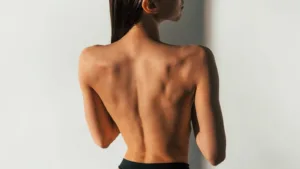

In a genetically ideal neck, these muscles are thin and lie flat against the floor of the mouth, allowing the skin to hug the jawline tightly. However, in many of my patients, these muscles are naturally bulky, rounded, or hang loosely. When this happens, they push outward, creating a persistent fullness or convex curve that ruins the sharp angle between the chin and the neck. This is structural bulk, not weight gain. Because this fullness is muscular, it creates a heavy appearance that no amount of surface-level treatment can resolve.

Why does liposuction fail to fix digastric muscle fullness?

This is the most common grievance I hear in consultations. Patients often undergo aggressive liposuction, expecting a chiseled look, but end up with a neck that still looks round or heavy. The reason is simple anatomy. The neck has distinct layers. Liposuction is designed to remove subcutaneous fat, which sits just under the skin but above the muscle layers.

The digastric muscle sits in the “deep plane,” protected beneath a sheet of muscle called the platysma. Standard liposuction cannulas cannot and should not touch this area. If you remove all the fat on top of a bulky digastric muscle, you actually make the problem more visible. The skin adheres directly to the round muscle, creating a “skeletonized” or unnatural appearance where the bulge is even more obvious than before. True correction requires us to go deeper and reshape the muscle itself.

What are the signs of digastric muscle hypertrophy?

Identifying whether your neck fullness is caused by muscle rather than fat is a critical part of the diagnosis. While an in-person examination is necessary for a final plan, there are several indicators that suggest the muscle is the primary issue. We look for specific physical characteristics that differentiate deep structural fullness from simple soft tissue redundancy.

Common indicators include:

- A sausage-shaped bulge on either side of the midline

- Hardness under the chin when swallowing

- Persistent fullness despite low body fat

- A rounded profile when tilting the head down

- Lack of pinchable soft fat in the central neck

How is digastric muscle reduction performed?

When we confirm that the muscle is the barrier to a sharp neckline, we use a technique known as tangential excision. The goal here is not to remove the muscle entirely, as it plays a role in stabilizing the jaw and swallowing. Instead, we treat the muscle like a sculptor treating a block of stone. We want to reduce its volume to create a more pleasing shape.

We access the area through a discreet incision under the chin. Once the muscle is exposed, we carefully shave down the outer, convex layer of the anterior belly. We typically remove the bulk that is protruding downward while leaving a healthy, continuous cuff of muscle attached to the bone. This significantly thins the “hammock,” creating a concave space. This new space allows the skin and overlying tissues to sweep upward and inward, creating that elusive 90-degree angle.

In cases where the muscles are not just thick but also separated, we use a “corset” technique. We suture the left and right borders of the muscles together in the middle. This tightens the entire floor of the mouth, much like lacing up a corset, and lifts the deep tissues upward to support the new jawline.